If you take a turn onto East Hermit Lane, just off of Henry Avenue after Henry Ave has crossed over going west from East Falls, and go down towards the site of the Kelpius cave, you’ll see on your left, on the east side of East Hermit Lane, a large stand of white pines. Some of them are quite large, over two feet across, and with a canopy dozens of feet above the ground, they tower above the house that’s there. Underneath them there is a ground layer with pokeweed, and jumpseed, and enchanter’s nightshade, and many other herbaceous plants, and there are also beeches and birches coming up in the understory. But the white pines dominate, in terms of the aspect of the stand, and in terms of sheer numbers and size.

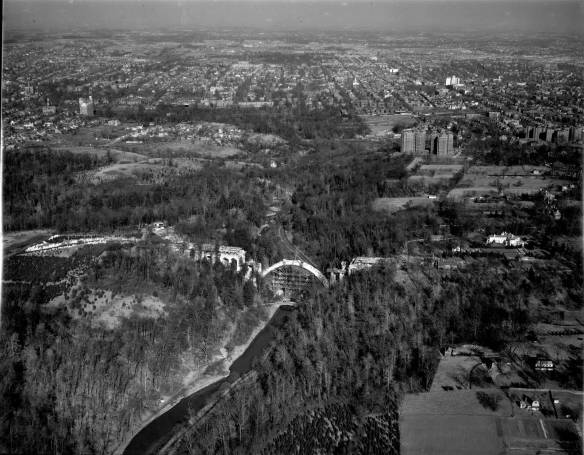

This stand is strikingly similar to one along Cresheim Creek, and based on their size, they (the ones along Hermit Lane, that is) were quite likely planted at a similar time as were the ones along Cresheim, and as is clear from the picture below, the Hermit Lane pines were there in 1931 which provides further evidence as to their age, and solidly provides an upper bound (of 1931) to their date of planting.

From the Library Company of Philadelphia Digital Collections: http://www.librarycompany.org/collections/prints/pr_research.htm

Aero Service Corporation, photographer; 1931 [The white pines are on the left side of the photograph, roughly midway between top and bottom of the picture, directly to the left of the Henry Avenue Bridge, which was being built at that time]

As was noted by John M. Fogg, Jr in his “Annotated checklist of plants of the Wissahickon Valley”, published in Bartonia (vol. 59) in 1996: “Although white pines may originally have occurred in the valley, the trees growing here today are the result of recent plantings. A fine grove exists along Hermit Lane near Hermit Street.”

If we look at a map from 1895, we see that this locale (where the white pines are) was privately owned at that time, and though, as we see from a map of 1910, the neighboring lots were part of Fairmount Park by the earliest parts of the 20th century, this particular site (again, where the white pines are) was not. If we assume that these trees were part of park plantings, and not plantings of private property, then this gives a lower bound of 1910 for the year of planting for these trees (given that the property was not part of the park in 1910, as indicated by the maps linked to above), thereby further supporting the argument that these trees date to the vicinity of about a hundred years, again, much like the white pines of Cresheim Creek. And if we look again at that 1931 aerial, above, we see that the stand extends across the path that divides what was private property in 1910 from what was park property at that time. This further implies that the planting was associated with the park, and therefore would postdate the time when that lot became part of the park.

If we look at an aerial photo from 1937, then we see that the stand of white pines is visible, and quite prominent – densely packed in, and of a reasonably appropriate size for stand in its mid-twenties. The second portion across the path is still there, visible in that 1937 photo, too. And if we look at aerials from 1942 or 1957, we see that this stand of white pines is clearly apparent there, along with the portion to the southwest, across the path (it is no longer there today). [to browse more aerial photos, see here: http://www.pennpilot.psu.edu/ ]

Something that we see as we look at these aerials across the 1930s to the 1940s to the 1950s, in addition to the stand itself, is also the wooded areas around it and nearby. And from this we see that as the pines that were planted there grew, that there were wooded areas surrounding them, and they were growing too, until that landscape today yields an appearance of continuity – it is all “the woods”, even if some parts of them look a bit different from one another. And if we walk there today, it can seem like the woods have always been there, in these large expanses, and that they are “natural”, in the sense of not having been made by people, that they just kind of got there on their own and that they keep on going and growing, all on their own. After a century or so, it all just looks like woods, and the kind of woods that we might imagine has always been here. [NB: we heard Pine Warblers here on the 10th and the 13th of April, 2014 – and so one might say that the birds see the pines, too [note that Pine Warblers are not listed as being in Cresheim Creek, where there’s another thick white pine stand, in J. C. Tracy’s paper “the Breeding Birds of the Cresheim Valley in Philadelphia, 1942“, published in Cassinia]; I’ll note also that at this time (the 13th of April), along the Wissahickon, near and downstream from the Henry Ave bridge, that bloodroot and trout lily and spring beauty were all in flower and that Podophyllum was beginning to leaf out, too]

If we look a a photo from 1911, of the Lotus Inn, we see that there were a fair number of trees down in the ravine:

http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/idno/458

The above photo was taken a bit downstream from the Walnut Lane Bridge; it’s where the Blue Stone Bridge is now; that bridge was the continuation of the road you see there in that photo – it’s now the trail that leads up to the Henry Avenue golf course (it used to be Rittenhouse Lane). That is, it’s just a bit away from where the white pine stand of Hermit Lane is now. [I’ll note also that it looks like there’s hemlocks there, too]

More broadly, looking around Philadelphia today, along the Wissahickon or the Pennypack, or in the wooded areas of West Fairmount Park or Juniata Park, or throughout so many of the many other parkland areas currently in Philadelphia, we see forests, and it can seem some times as though that it how it has always been.

Certainly, when William Penn arrived here in the 17th century there were woods woods woods and more woods, filled with all kinds of trees. But by the 20th century, these had been cut over, multiple times (see page 39, here, for more about this), and also just prior to and at that time (the late 19th and into the 20th century, that is) was a period of incredibly extensive development across Philadelphia, and therefore wooded areas were being rapidly cleared to accommodate housing, and also businesses and industry – the economic drivers of a thriving city. This period was an intense time for this – there was roughly a doubling of the population of Philadelphia between the 1850s and 1890 (according to US Census data), when we went from about a half a million to about a million people, and then the population roughly doubled again, until we hit about two million people in the mid-20th century, and one need not imagine the impact this would have on the woods, this massive population expansion. We can also see this expansion of urbanization in the reduction of farms and farmland here – we go from 824 farms in Philadelphia in 1910, to 423 in 1920, to 381 in 1925 (data from the 1925 Census of Agriculture), which represented a reduction in farm acres in Philadelphia from 30,488 acres, to 17,408 acres, to 15,971 acres at each of those steps (Philadelphia’s total land acreage is about 82,000). By the 1950s, this had declined yet more, to 76 farms (5,024 acres) in 1954, and 53 (3,465 acres) in 1959; as of the latest census of ag, in 2007 there were 17 farms comprising a total of 262 acres. (for more historical ag census data, see here: http://agcensus.mannlib.cornell.edu/AgCensus/homepage.do, and for current and more recent: http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/index.php; specifically for Pennsylvania: http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_2_County_Level/Pennsylvania/; additionally, in 1911 there were 1,474 license issued to “farmers”, according to the Annual Report of the Bureau for City Property for the year 1911). Transportation affected this as well – farms could move out of cities because of improved transportation (e.g, train lines), which could move food quickly across long distances (and with the advent of the refrigerated rail car in the 1890s, this adds in to the calculation as well). Also, in the 20th century, with the shift from horses to cars for transportation, the decrease in the horse population numbers would have meant a reduced need for hayfields, and so as fewer horses were fed, farmland (for hay, in this case) would have had less of an economic simulus to stay open. (for an article on horses and cities, see: American Heritage Magazine, October 1971)

At the height of our deforestation rate, in the mid-19th century, a wooded site in our region would be cut about every 25 years (for a 4% (that is, 1/25, or one out of every twenty-five years) deforestation rate). These woods that were being trimmed on the scale of decades were or had been cut to clear land for development, and for farmland, and to build houses (and for other lumber needs, like furniture or cabinets and what-have-you), and also for firewood, wood being the dominant energy source in the US pretty much through to the end of the 19th century, as can be seen in figure one, here; stoves also had an impact, as can be read about in “Forest Conservation and Stove Inventors: 1789-1850” [by William Hoglund, 1962]), and so it’s not like there would have been a single episode of cutting at a site as land was cleared and houses were built from those trees that were cut, and then everything then would have commenced back to growing into woods again, but deforestation was a continuous local process at that time, due to energy needs, as well. (e.g., as the use of coal increased, the cutting of wood for fuel would have decreased, thereby increasing forestation) [They were also cut for other reasons, even amidst revolution, as John Thomson Faris relates in his 1932 Old gardens in and about Philadelphia and those who made them: ‘…in 1782, the Corporation of Philadelphia ordered that all trees in the streets of the city be cut down, because “they obstructed the prospect and passage through the public streets, lanes, and alleys,…disturbed the water-courses and foot-ways by the extending and increasing of the roots.” Then it was felt that they were apt to “extend fire and obstruct the operation of the fire engineers.” Then, with rare humor, the additional indictment was given: “They were not affected to the government because they remained with the enemy when they had possession of the city!” ‘ …. Faris goes on to write that “Fortunately the strange law was repealed in season to save some of the trees that were the glory of the streets of the city.”]

By the late 19th century, the deforestation rate had slowed a bit, to about 2%, but that still means we’d expect stands to be at most about 50 years old at that time, in the late 19th and early 20th century, which is the time when we see the oldest portions of the lands that are now forested in Fairmount Park becoming the natural areas that we now know them as.

That is to say that Fairmount Park was still quite young, by arboreal standards, as the 20th century arrived and moved forward – the oldest parts of it were on the order of a half century old at that time (dating to roughly the mid-19th century, that is), and many large parts were still coming to the city as the 20th century rolled on (for example, like the Pennypack, whose land starts being acquired by the city in 1905, and of course the site upon which the Hermit Lane pines now stand comes to the city around this time), and so the woods of Fairmount Park that we see now, filled with enormous tulip poplars and oaks and pines, and hemlocks, too, would have been pretty young at that time, and nowhere near as full as what we see today.

I’m not aware of any stands in Philadelphia that are older than 100 to 150 years old, and this is pretty well in line with the historical data outlined above. This is not to say that there aren’t individual trees that are older than that, as we know that there certainly are ones much older than this (e.g, in Hunting Park), or even some groupings of older trees (e.g, if you go along the rocky hilltop trail along the Wissahickon, just north from the Henry Ave. Bridge, there’s some wonderfully old chestnut oaks growing among the rocks overlooking the Wissahickon there that, based on their size, quite clearly predate the late 19th century), but I’m not aware of any substantial stands of trees in Philadelphia that predate the late 19th century.

And so we see in the first half of the 20th century a low of the areal extent of the forestation of Philadelphia – the woods had been cut over multiple times by then, and older stands that might have been found in less populated areas, perhaps distant out in the far northeast, or way out in the wilds of west Philadelphia, both dry and wet, were being cut down for the development that accommodated our growing population, and the current grandeur of Fairmount Park was still a young sylva at the time, not yet grown to the size that we see now.

In the 1930s especially, it appears, Philadelphia had few forested areas – development had extended to parts of city that still had wooded spots, and Fairmount Park had not yet become the well forested agglomeration of sites that we know today. Though it can seem difficult today to believe that our green city was once so unwooded, an illustrative anecdote of this is provided in Richard Miller’s paper, “the Breeding Birds of Philadelphia”, in volume 51, number 7 of the Oologist (“for the student of birds, their nests, and eggs”), published in 1933, where he notes of the American Crow that it is “Common, but slowly decreasing, due chiefly to destruction of woods.” (I also note that the Red-Bellied Woodpecker, a bird of forests and woodlands, is not listed in Miller’s paper – this is a bird that I commonly see now, along the Wissahickon, and elsewhere (e.g, at Bartram’s Garden, on the 5th of April 2013), which calls to the increase of trees in Philadelphia, I note; this is a bird whose range has expanded northward generally in the past decades, I also note; NB: notes are good).

Nowadays, so far as I am aware, no one fears for the crows due to lack of woods, and in this we can see the change from then to now – today there are wooded areas throughout the city, from Cobbs to the Poquessing, and so many places in between, where there are not just trees, but forests, and woodlands. Our landscape has changed drastically from a century ago – the woods we see now have grown since then, and what were once open areas are now wooded. Of course, the opposite has also occurred – what were once wooded areas now are not, and are now populated by buildings or streets or mown parks (sometimes this happened with quite a bit of opposition, as the fight over “Sherwood Forest” prior to it being cleared illustrates), and so it’s not like the woods have all grown up everywhere throughout Philadelphia, but as those wooded areas were being cleared, elsewhere parklands grew, and weren’t then cut again to clear the land, or for timber and fuel, and so we see this striking change throughout the landscape, from a hundred years ago to today.

All of this change might make one wonder about ticks, for example Ixodes scapularis, the black legged tick; this species was named and described by Thomas Say, and that was done in the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (Vol. 2, 1821: pp. 59-83 – thanks to Ken Frank for pointing this out to me, by the way). Say mentions of this species: “Rather common in forests, and frequently found attached to different animals.”

There also were differences in wetlands, between now and a hundred years ago, as is indicated by the inclusion of Typha angustifolia and “Phragmites Phragmites” (i.e., Phragmites communis), in Thomas C. Porter’s “Rare Plants of Southeastern Pennsylvania”, which is in the Botany Libraries at Harvard (it has a publication date of “March, 1900”). These wetland plants are quite common in Philadelphia now. An indicator of changes in wetland quality in the Wissahickon is that Chrysosplenium americanum, an indicator of pretty nice wetlands, was collected in the Wissahickon in the 19th century (by J. B Brinton on the 10th of June 1888 [with “fruit”, as indicated on the herbarium sheet], and by Albrecht Jahn on the 5th of May 1895 – both of these collections are at PH), but hasn’t been seen there recently.

And there are plants that we likely have fewer of now, most likely due to increased forestation (succession, that is) and development – like Hypericum gentianoides, which does occur in Philadelphia today (it was flowering in Haddington Woods, out by Cobbs, on the 2nd of September 2015), but we don’t see it often. Barton (1818), however, notes it as: “In exposed situations on sterile soil; generally on roadsides; not uncommon.”, and it is included in Keller and Brown (1905), and Rhoads and Block note it as being “common” (though this is not a particular note about Philadelphia). Also, in the Plants of PA database, there are multiple entries, indicating that it was collected multiple times in Philadelphia (from: Byberry, Cedarbrook, Germantown, Holmesburg, Mount Airy, Olney, Shawmont, Wissahickon Creek, Cedarbrook, Germantown), and in the herbarium of the Academy of Natural Sciences, there are multiple collections, one of which has on the label:

“Remains of last year’s plants forming almost pure stands in open

Coastal Plain sand-gravel; growing out of a covering of Cladonia.

This area was formerly covered by timber but is doomed to destruction

by real estate development. S. W. corner of Cheltenham Avenue and

Easton Road.

Cedarbrook.

J. W. Adams 48-33

April 6, 1949”

There are 6 more collections at the Academy, whose labels read: 1) “1 Aug 1849 Germantown” by “R. C. Alexander”; 2) “Dry Sandy Soil / Olney, Phila Co. / July 30, 1922 / Collected by R. R. D.” [= R. R. Dreisbach] coll# 1-155; 3) “above Shawmont, e. side / Schuylkill. Phila Co Pa / Collected by S. S. Van Pelt / Aug 5 1902”; And another: 4) Wissahickon, coll: S. S. Van Pelt – Aug 15 1902; 5) “Openings between coarse grass tufts on sandy slope 3/4 mile south-southeast of Byberry / Edgar T. Wherry / September 19, 1954”; 6) “Weedy roadsides and old fields / 1 mi. n.e. of Mt. Airy / Florence Kirk / August 3, 1949”

And so we see that this plant of open places was historically pretty common, though it does not appear to be quite as common as it once was, here in Philadelphia.

There is, I should say, also continuity through time here – hemlocks have been here and are here now. And many other plants, animals and fungi have been documented to have been here in the past and remain here to this day. These include plants that are parasitic upon other plants – these persist as well, such as Conopholis americana, or Squaw-root, noted by Keller and Brown (1905) with a locality of “Wissahickon”, and that Barton (1818) noted as “Parasitic. On the authority of Mr. Bartram, I have introduced this plant, never having met with it myself. He says it grows in the woods near Philadelphia. Perennial. July.” (however, in Norman Taylor’s 1915 Flora of the Vicinity of New York, which includes Philadelphia, he lists Conopholis americana for PA as “Bucks, Delaware, and Chester Counties” (that is, not Philadelphia); he also calls it “A rare and local plant” and its habitat as “In rich woods, usually at the bases of oak trees… Rare”; in Rhoads and Block (2007), the Plants of Pennsylvania, they note of squawroot: “parasitic on Quercus spp.; occasional in forests, mostly S and W”). [one wonders if this plant’s populations have grown more abundant in the past hundred years due to expansion of oak populations which grew due to decrease in population of their main competitor, the American chestnut, which decreased due to the introduction of the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica, the causative agent of the chestnut blight, doesn’t one?]

And there are plants that we still have, but in very different places, as we can read from Bayard Long’s 1922 paper in Rhodora (vol. 24), “Muscari comosum a new introduction found in Philadelphia” [the common name for this plant is grape hyacinth]:

“The collector of the specimen of Muscari comosum, Miss Adelaide Allen, fortunately was able to designate exactly where it had been obtained, as the spot lay along the familiar route from her home to school. Through her kindness, and the interest of Dr. Keller, we learned that it grew along the sides of a dyke, running in to South Broad Street from outlying farm houses, near League Island Park, in the southern portion of Philadelphia. This area consists in large measure of the extensive alluvial flats and marshes of the lower Delaware, more or less intersected by ditches. The region is not yet built up to any extent and the more elevated portions are frequently occupied by truck-farms. The southern extension of Broad Street, with its trolleys, offers one of the chief lines of travel in this particular locality, and the nearby farms often obtain access thereto by dykes laid down over the low meadows and more impassable places. These dykes are continually augmented by the dumping of ashes and rubbish down their sides. [note that the Dr. Keller mentioned above is the same Keller of ‘Keller and Brown’, mentioned previously]

In such a habitat from a detailed sketch map furnished by Miss Allen the Muscari was found growing.”

This plant persists from then, as is noted by John M. Fogg, Jr in his “Annotated checklist of plants of the Wissahickon Valley”, published in Bartonia (vol. 59) in 1996: “Muscari botryoides. Grape-hyacinth. Introduced and naturalized from Europe. Occasional in woods and clearings. Thomas Mill Road.” (and it still persists to this day – on 14th of April 2014, it was flowering quite well along the Wissahickon, for example in the floodplain just downstream from the Walnut Lane Bridge; it was flowering here the week of the 13th of April 2015) [note also that League Island Park was relatively recent, in the 1920s, having been acquired by the city in the 1890s by purchase/taking of a variety of tracts (total initial cost: $399,670), as provided by an ‘Ordinance of March 11, 1895, “appropriating League Island Park as an open public place for the health and enjoyment of the people.” ‘ (Appendix to the Journal of the Common Council, 1897-1898)]

And there are animals that also span the temporal divide – consider the Virginia opossum which, as is noted in Whitaker and Hamilton’s Mammals of the Eastern United States (3d edition; 1998), can live many places: “The opposum’s adaptability to a great variety of habitats, ranging from forest to purely agricultural lands, explains its success in the eastern United States. It is often quite common even in urban or suburban areas, and many are found dead on the highways.” and “The opossum is a solitary wanderer, remaining in no one place for long, and may be found far from trees. Its daytime den is in a fallen log, a hollow tree, a cleft in a cliff, a brushpile, a tree nest of a bird or squirrel, a woodchuck or sun burrow, or a recess under a building, or in many of other protected situations. Opossums do not dig their own dens, and thus are dependent on other animals, primarily the woodchuck and skunk, for ground burrows.” – they mostly den in wooded areas, arboreally as well as on the ground (and “in snags and leaf nests probably used or constructed in years past by squirrels”), though they have also been reported to den in an old field.

This marsupial adaptability is reflected in the current presence of numerous opossums (opossa?) in Philadelphia today and their presence a century ago, as we see evidenced in the number of individuals presented to the Philadelphia Zoo for accession to its menagerie, in the early part of the 20th century, that came from Philadelphians – for example, from the “List of Additions to the Menagerie during the Year Ending February 28th, 1914”: “1 opossum presented by G.W. Cassel, Philadelphia.” (13 November) and “1 opossum ([male]) presented by Mrs. George Biddle, Philadelphia.” (9 December) and “1 common opossum ([male]) presented by Harry Rathbone, Philadelphia.” (13 January) and “1 common opossum ([male]) presented by Miss Theresa Hayes, Philadelphia.” (22 February); or for the year ending February 28th, 1914: “1 common opossum ([female]) presented by Walter Ellis, Philadelphia.” (13 March) and “1 common opossum ([female]) presented by Mrs. Harrold E. Gillingham, Philadelphia.” and “1 common opossum ([male]) … presented by Frank G. Speck Philadelphia.” (22 November) and “1 opossum ([female]) presented by Mrs. A. H. Gerhard, Philadelphia.” (1 December) and “1 opossum ([male]) presented by William F. Girhold, Jr., Philadelphia.”; and for year ending February 29th, 1912: “1 opossum presented by Master Ralph Fritts, Philadelphia.” (13 May) and “1 opossum presented by Guy King, Philadelphia.” (28 December) and “1 opossum presented by Mrs E. A. Cassavant, Philadelphia.” (4 February) and “1 opossum presented by The Walter Sanitarium, Walter’s Park, Philadelphia.” 18 February) and for year ending February 29th, 1920: “1 common opossum presented by Thomas Oakes, Overbrook, Pa.” (12 April) and “1 common opossum a presented by Dr. Frank Fisher, Philadelphia.” (3 October) and “1 common opossum ([female]) presented by John A. Caraher, Philadelphi” [sic] (30 November) and “1 common opossum (male) presented by John J. Daly, Philadelphia.” (23 February). All these and more can be read in the Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Zoological Society of Philadelphia volumes 40-49; be sure to note also how many people from Philadelphia were donating alligators in those years. Note also the numerous birds and other animals that were either “caught in the garden” or “found in the garden” (including at least two screech owls).

While the above mentioned animals were caught and presented live to the zoo, I do want to note that opossum were hunted and eaten here historically, as well, as we can see from an 18th century letter from Father Joseph Mosley, to his sister (writing from St. Mary County, Maryland – 1st of September 1759; the following letter was published in the Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Volume 17; 1906)

“Our game is very plentiful, as in shooting possums, deers, wild turkeys, raccoons, squirrels, pheasants, woodcocks, snipes of different sort, teal, wild ducks, wild geese, partridges, &c., but all different from birds of the same name in England, and all very good eating except the raccoons. Panthers have been seen in this country, but not of late years. We have turtles, or tortoises, of all sorts We abound with all sorts of fruits, so as even to feed the hogs with peaches that would sell very dear at your market.”

You’ll notice that deer are on that list, and second only to possums – these animals are quite common now in Philadelphia, but this was not always the case, as is evidenced by the purchase of a male white tailed deer by the Philadelphia Zoo, on the 4th of April 1911, as is noted in the Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Zoological Society of Philadelphia volumes 40-49; “List of Additions to the Menagerie during the Year Ending February 29th, 1912” … “1 white tailed deer ([male]) purchased.”)

I’ll note here that peaches, mentioned in Father Mosley’s letter, though an introduction from the old world, have been here for quite some time – Peter Kalm mentions them multiple times in his Travels into North America; they are mentioned by Peter Collinson in letters he wrote to John Bartram; and William Penn mentions them in one of his letters home: “Here are also peaches, and very good, and in great quantities, not an Indian plantation without them; but whether naturally here at first I know not.“ (extract from “A Letter from William Penn, Proprietary and Governor of Pennsylvania in America, to the Committee of the Free Society of Traders of that Province, residing in London,”).

But back to the opossum – while this animal was present here, it was not quite as common towards the mid-part of the 20th century as it is now, as is noted in Philadelphia: a guide to the nation’s birthplace (1937; Pennsylvania Historic Commission and Federal Writer’s Project):

“With so much of the wildwood atmosphere still preserved, Philadelphia has its share of bats, squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, weasels, and the smaller rodents, such as the meadow mouse and the white footed deer mouse. The raccoon and opossum are now rarely found, but are still encountered in the deeper rural sections of this district.”

And so, in the overall change of Philadelphia’s ecosystem over the centuries, many of the moving parts have remained, though they may have shifted gears a bit.

This succession, the change in urban ecosystems through time, is not, as is illustrated by the Hermit Lane pines, strictly a passive process. It is, or at least can be, actively facilitated by people and their (or “our”, I should say, since we are all people) management – by planting those white pines, for erosion control or for reforestation, this altered the pattern of succession that we would have seen otherwise, from what we most likely would have seen, or at least what I’d expect to see, which would be a stand of tulip poplars, that would’ve now had trunks about a meter across and would now be just about reaching the end of their lifespan, to this massive stand of white pines that we see today. This occurred not by chance, but by human intervention, and is the reason that what we see today is there as it is.

By looking at these old photos and maps, by reading old reports and census documents, by understanding landscape ecology and succession, we can see how what was done before has brought about what is here today – we can see the enormous changes that have affected our city, and often be quite surprised at just what those changes were and how they came about.

It can be surprising to realize that Philadelphia has more dense forest today than it did a hundred years ago, and also then to learn the other impacts this brings about, on birds, as mentioned above, and also on water quality, among other environmental factors. And it is key to realize that this did not happen by chance; ecology in cities is due directly to actions by people, and always has been, for a very long time, as we see from those pines that were planted a century ago. We are part of these ecosystems, and thoughtful decisionmaking, such as that in the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation’s recently released Parkland Forest Management Framework, is needed for making these decisions in a way that will be amenable to all of us in and for Philadelphia, both now and in the years, decades, and centuries to come.