Cresheim Creek is a tributary of the Wissahickon, and where these two waterways meet is called Devil’s Pool. People have been swimming at Devil’s Pool for centuries, diving off the high rocks and into the deep pool below, having cookouts on the side, and sitting in the cool water on the hottest of summer days – it’s been like this for hundreds of years, cool water on a hot day has always drawn us to it, and probably always will. That cool water carousing out of Cresheim Creek runs down all the way from Montgomery County, where the headwaters of Cresheim spring forward, up near the USDA research facility on Mermaid Lane. That water quickly cuts into Philadelphia, running alongside an old Pennsylvania Railroad spur that came off of the Chestnut Hill West line, a spur jutting off that main branch, popping off in a northeasterly direction – its railbed then crosses Germantown Ave and ducks underneath a trestle of the Chestnut Hill East line, which was a Reading Railroad train. These lines and companies didn’t touch, but where they came close to each other, Cresheim Creek ran beneath them just the same. And while that old train bed along which Cresheim Creek flows doesn’t run rails anymore, it is still there, a remnant of a time when trains lined the city in far higher resolution than they do today, and of a time when they followed streams instead of piling over them.

Thomas Moran’s painting Cresheim Glen, Wissahickon, Autumn captures how this waterway looked in the mid to late 19th century, with a white oak to one side (the viewer’s left), a sycamore to the other, tumbled rocks in the water, and a wide open space just beyond. As it rolls through Philadelphia, Cresheim Creek runs alongside Cresheim Valley Drive, cutting through deep rocks, and then into a wider plain. At about this opening, just southwest of the train bridge for the Chestnut Hill West line, there used to be a recreational lake, called Lake Surprise – this was there about a hundred years ago and is no longer there. Lake Surprise was constructed after factories upstream, like the Frances Carpet and Dye Works, had closed, thereby keeping the lake’s patrons unstained.

Cresheim Creek used to have quite a bit of manufacturing – below where Lake Surprise once was, and just southwest of the McCallum Street bridge, there was a paper factory up until as recently as about a hundred years ago. While none of those mills or factories remain today – Cresheim Cotton Mills and Hills Carpet Factory have long been closed – evidence of them is still clearly there, as you walk along stone roads in the middle of the wooded banks of the streams. This is especially noticeable southwest of McCallum, southwest of where Lake Surprise used to be, where cut and trimmed rocks line paths that once carried wagons to and from the mills and are now sitting overgrown, with plants diving in from the sides. A stone bridge used to cross the creek, just downstream from where the McCallum Street bridge passes far overhead; that stone bridge, whose remnants still remain, was crumbled in a flood in 2004. To see what that area under McCallum looked like in the 19th century, see here: http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/224 )

Further onwards, downstream, towards the Wissahickon, past McCallum, there is a dense woods on either side of Cresheim – as you look you’ll see reminders of the horticulturally developed areas nearby, plants such as a Styrax (planted about 16 years ago – we cored it to find out), a hardy orange (Poncirus trifoliata), and many once-cultivated viburnums that have escaped into the woods; all of these are there and kind of pop out at you, if you’re looking. There are also hundreds upon hundreds of other plants that came in with a bit less of our help – beeches and birches and ferns and flowers that seeded or spored in due to the efforts of the wind, water, or animals other than humans, and though sometimes they might’ve had some help getting to this area, some have figured out how to get around on their own, like the umbrella magnolia, for example. (I note here that, as Rob Loeb has sagely pointed out to me, in Fairmount Park it is often unclear whether a plant was planted by people or not – for example, we generally say that beeches on rocky slopes came there on their own, however, beeches were planted in the early part of the 20th century, and trees we see now may well be remnants of what were planted by people at that time, in what is appropriate habitat for that species; for an example of documentation of beech planting for forestry, see Joseph Illick’s “Pennsylvania Trees”, printed in 1928 [“Reprint of Fifth Edition of 1925”, Bulletin 11, PA Dept. of Forests and Waters], where the caption to Fig. 29 (“Thinned Scotch Pine”) includes the following: “About 70 years old. Underplanted with Beech”)

And there are even plants here that are parasitic upon other plants, such as Conopholis americana, or Squaw-root, noted by Keller and Brown (1905) with a locality of “Wissahickon”, and that Barton (1818) noted as “Parasitic. On the authority of Mr. Bartram, I have introduced this plant, never having met with it myself. He says it grows in the woods near Philadelphia. Perennial. July.” There are also plants that were once here that we no longer see, like the pawpaw (Asimina triloba), which I have yet to see growing in the Wissahickon or along any of its tributaries, but if we take a look at Barton (1818), we find that it was here:

“Papaw-tree is very rare in this vicinity, and here its fruit seldom comes to maturity. It is a very small tree, with deep brown unhandsome flowers, and an oblong fleshy esculent fruit, about three inches long, and one and a half in diameter. On the Wissahickon; and on the road to the falls of Schuylkill, west side of the river, and about three miles south of the falls; scarce”

Keller and Brown (1905), in their flora of Philadelphia, list a locality of “Wissahickon” for the paw paw, but it is not to be found in Jack Fogg’s checklist of plants of the Wissahickon (published in 1996 in Bartonia), and as just mentioned above, I haven’t seen it here (though it does grow elsewhere in Philadelphia today).

And so the plants have changed – some that weren’t here historically are here now and some that were here previously no longer are. But the forest is still here, in a variety of different forms and structures. One spectacular stand of woody plants is up a hill that is somewhat steep, and not too far southwest from McCallum Street, and on the southeast side of the stream. There, there is a magnificent stand of mountain laurel, flowering in the spring underneath very large chestnut oaks. These might have been planted. They might not have been planted. But either way, they flower in the spring and as they shed their leaves in the fall they leave behind magnificently crooked branches straggling towards the canopy above.

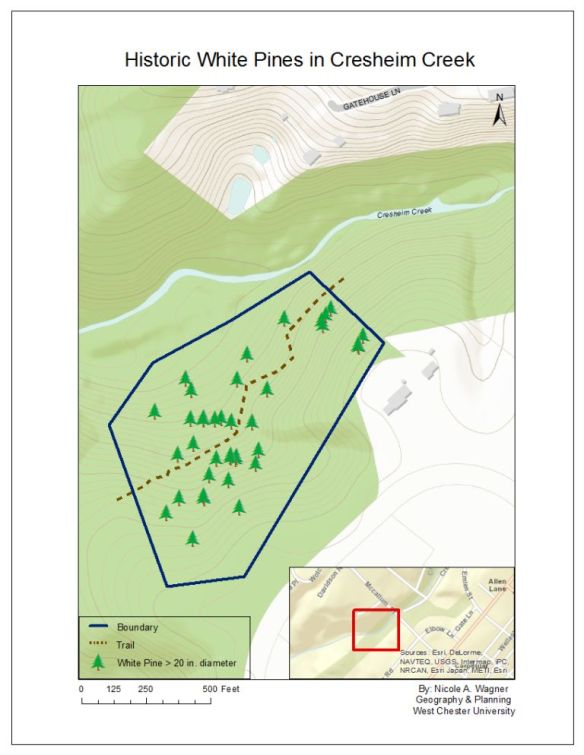

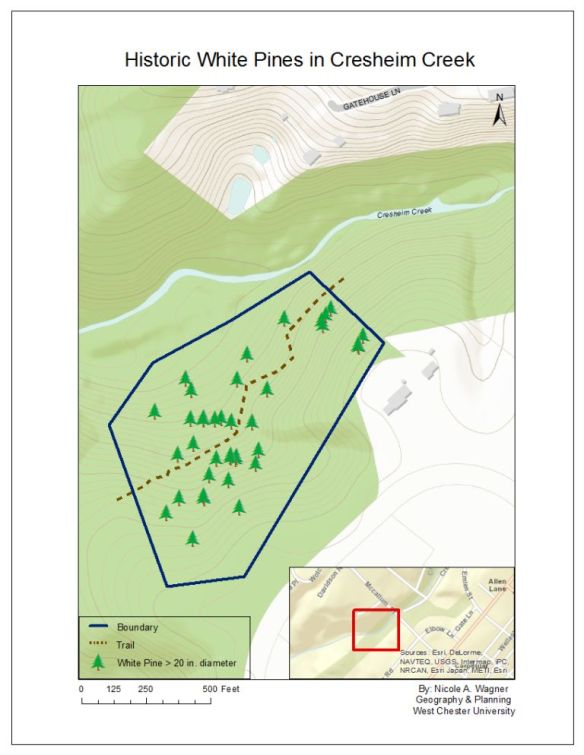

A little bit farther downstream from there, downstream from that stand of mountain laurel and chestnut oak, but before you get to the Devil’s Pool where Cresheim Creek empties into the Wissahickon, there is a dense stand of eastern white pines (Pinus strobus), a stand filled with very large trees. Many, if not most, of them are well over 2 feet across and tower a hundred plus feet over your head as you walk among them. It is a uniform stand of trees, pretty much all white pines, with their soft needles making for quiet walking along the paths that wander over their roots, and very little underbrush to block your way. I’ve been coming to Cresheim for years, and this site is one of the most striking there – and for many years, I’d thought of it as a scene right out of pre-colonial Philadelphia, before there was a Philadelphia. This was how it must have looked, I thought. Enormous white pines, tall like the ship masts they would’ve become if this were three hundred years ago, filling in the woodland scene. White tailed deer would’ve run beneath, turkeys would’ve gobbled in there, too – this would’ve been nature at its cleanest, its purest, its finest. This is how Cresheim Creek must’ve been , I thought, and how much of the Wissahickon would’ve looked before we got here. But that’s not how it would have been, not even close. Unknown to me then but known to me now is that the white pine is not native to Philadelphia. While it is native to Pennsylvania, it is not native to our city – it was not here, most likely, when Europeans arrived, and it quite certainly didn’t fill thickly the woods with uniform stands, like this stand at Cresheim Creek does today.

How do we know this? Well, one reference to use to answer this kind of question is William P. C. Barton’s Compendium Florae Philadelphicae, written in 1818. Dr. Barton was the nephew of Benjamin Smith Barton, the man who trained Meriwether Lewis in botany, and the younger Barton was also a botanist, at the University of Pennsylvania, just like his uncle. And he (William P. C., that is) wrote a book that listed all the plants in Philadelphia at his time. Pitch pine (Pinus rigida) is there, and even noted as being “on the Wissahickon”. So is what was called at the time yellow pine, but we now call short leaf pine (Pinus echinata – though Barton calls in Pinus variabilis). But the eastern white pine, Pinus strobus, is not there, it is not listed in Barton’s flora of Philadelphia. And so we can reasonably confidently say that this tree was not here in 1818. Addtionally, Peter Kalm, Finnish botanist and student of Linnaeus, when he was here in the late 1740s, he didn’t see it, though he did see it in Albany in June 1749, writing “The White Pine is found abundant here, in such places where common pines grow in Europe. I have never seen them in the lower parts of the province of New York, nor in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” (Travels into North America, by Peter Kalm, translated by John Reinhold Forster); he most likely would have noted such a valuable tree, and where it was, and so this is further evidence that this tree wasn’t here. (this was a tree of great value, so great that in 1710 there was passed in England: “An Act for the preservation of white and other pine-trees growing in Her Majesties colonies of New-Hampshire, the Massachusets-Bay, and province of Main [sic], Rhode-Island, and Providence-Plantation, the Narraganset country, or Kings-Province, and Connecticut in New-England, and New-York, and New-Jersey, in America, for the masting Her Majesties navy “) Additionally, in Ida A. Keller and Stewardson Brown’s 1905 Handbook of the Flora of Philadelphia and Vicinity, published by the Philadelphia Botanical Club, they do list the eastern white pine, and note it as being present in Bucks County, and Montgomery County, and Delaware County, and Chester County, and Lancaster County, and Lehigh County – throughout southeastern Pennsylvania, you’ll note. Except in Philadelphia. And in Thomas C. Porter’s 1903 Flora of Pennsylvania, he lists it as being in Chester and Lancaster and Blair and Huntingdon and Montour and Erie and Tioga and Delaware and Luzerne and York and Allegheny counties. But not Philadelphia. And so, the evidence points pretty clearly to the eastern white pine, Pinus strobus, as not being native to Philadelphia County. We do see it growing naturalized here now, but it got here, to Philadelphia, with our help. It isn’t clear when it became naturalized (that is, reproducing and growing on its own) here, though it is pretty clear that this occurred by the 1960s. It is in Edgar Wherry’s “A check-list of the flora of Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania” (published in Bartonia, the Journal of the Philadelphia Botanical Club, vol. 38), and this came out in 1969, and there is a collection of Pinus strobus from Dr. Wherry in the herbarium of the botany department of the Academy of Natural Sciences (PH) with label data stating: “Seedling from old (though probably planted) tree, Schuylkill Valley Nature Center, 1 mile west of Shawmont / October 27, 1967” (NB: this is the only collection of P. strobus from Philadelphia at PH, and I also note that there are none from Philadelphia at GH; I looked in June of 2013. There are three listed in the NYBG online database, one collected by Isaac Martindale, July 1865, in Byberry, but it is not noted if it was cultivated (NB: Martindale commonly collected in gardens, as is noted in Meyer and Elsasser 1973 [“The 19th Century Herbarium of Isaac C. Martindale”, Taxon 22(4): 375-404]: “His earliest collections date from 1860 when he started to collect plants in his garden and environs of Byberry and from the garden of his uncle, Dr. Isaac Comly, who also lived at Byberry. Martindale left a fairly good record of cultivated plants of the Bartram garden in Philadelphia, of Thomas Meehan’s nursery in Germantown, Pennsylvania, from his own garden, and from other gardens in the Philadelphia area.”; additionally, this species has been commonly planted in the region for quite some time, e.g, as is noted in William Darlington’s 1826 Florula Cestrica, of Pinus strobus: “This is a handsome tree; and when met with, is generally transplanted about houses, as an ornament.” – he also notes it as being ‘rare’ [this refers to Chester County, PA]); there are two additional collections of P. strobus from Philadelphia, at NYBG: two duplicates of var. “fastigiata”, collected in 1980 and noted as being cultivated). Also, in the archives of the Academy of Natural Sciences, there is a document, by Charles Eastwick Smith, a “Catalog of the phaenogamous and acrogenous plants (found within 15 miles of Broad and Market streets, Phila., and in the herbarium of C. E. S.)” … “found in 1860-1868”, and in it P. strobus (on p. 24) has a dash next to it, indicating its presence within that range at that time; however, there is no indication if it was in Philadelphia, or just nearby. And this stand itself has been documented as being planted, by J. C. Tracy, in his paper “the Breeding Birds of the Cresheim Valley in Philadelphia, 1942“, published in Cassinia, where he writes “Near the mouth of the creek a large stand of white pine has been introduced on the south slope.” Also, in Norman Taylor’s 1915 Flora of the Vicinity of New York, which includes Philadelphia, he notes of the range of P. strobus: “PA. Throughout”, but he doesn’t site any specimens or give details as to whether it was specifically found in Philadelphia; and so while this suggest that the white pine might have been naturalized here by 1915, it doesn’t suggest it strongly, and so it is as yet unclear as to when exactly this tree became naturalized in Philadelphia. But anyway… by the sixties it’s pretty clearly documented that it was naturalized here. But it most likely was not in the 19th century, the earliest 20th century, or before. Additionally, this stand in Cresheim Creek is an even-aged stand, most of them being about the same size (and therefore, by inference, all being roughly the same age), and most of them are on a hill, sometimes a pretty steep one.

And so this is pretty clearly a stand that was planted, because if it was a stand that had seeded in on its own, we would see trees of many different ages in there. And so, not only is it not a plant that was here prior to the 20th century, but this is not a naturalized stand either. People planted these. White pine was a popular plant to plant, about a hundred years ago, and that’s roughly (and the “roughly” part here will become more important later, by the way) when these were planted. At the turn towards the 20th century, the white pine was just so clearly a tree to be used in forestry, that a forester in Pennsylvania could write:

“It is not necessary to state the uses of this tree nor should it be necessary to state that it ought to be cultivated extensively. It is a rapid grower and prefers poor soil, yields early returns and is very valuable when mature – what more is wanted?”

(The above quote is from the “Statement of work done by the Pennsylvania Department of Forestry during 1901 and 1902, together with some suggestions concerning the future policy of the department, and also brief papers upon subjects connected with forestry.”, Chapter VII “Propagation of forest trees having commercial value and adapted to Pennsylvania.”, by George Wirt, Forester – this work can be found in the library of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia) As we see, white pines were commonly planted about a hundred years ago, and this is an even aged stand of about that age, and therefore it is quite clear that this stand of white pines was planted, and didn’t seed in on its own. Additionally, as Alexander MacElwee writes in the “Trees and Wild Flowers” section of T. A. Daly’s “The Wissahickon”:

“White Pines are frequent. In recent years thousands of seedling pines have been planted with a view to reforesting naked slopes. These consist principally of the White Pine, Red Pine, Jack Pine and short leaf Yellow Pine.”

OK, so this is a plant that is not native to where it is now planted, and it was planted by people. Also, it is on a hill, so it was most likely planted to control soil erosion, which further implies that it was planted not so much for a “natural” aesthetic (though that may well have been part of it), but moreso for a civil engineering project. It is a wonderfully beautiful stand that really does make us think about what is “natural”, just from what we have seen of it so far. But that isn’t all. Additionally, the seedlings that were used to plant this stand were quite possibly imported from Germany. Up until roughly (and again, that “roughly” will be important in a bit) a hundred years ago, many if not most of the white pine seedlings planted in the US were imported. Why? Why would Americans import, from thousands of miles away, a tree that is native to the US? Because it was cheaper. Germany, and a few other countries, had the comparative advantage in terms of skilled labor and economics of scale, and foresters in the US took advantage of that, buying in the less expensive, high-quality imports from across the sea. An article written by Ellicott D. Curtis, published in Forest Quarterly, volume VII, from 1909, clearly outlines the economics of this. He quotes a cost of 95 cents per thousand for white pine seedlings in Germany – he then cites freight costs as 50 cents (to New York) and duty as $1.15 (for import into the US), for a total cost of less than $3 per thousand, as the sale price in New York. He contrasts this with prices from various American producers, the lowest of which is $5 per thousand (from Harvard Nurseries in Harvard, Illinois). Even with transport costs and duties, it was still cheaper to import from thousands of miles away. Curtis also notes the low volume of US production:

“I desire further to call attention to the fact that the raising of trees for forest planting is a comparatively new industry…”

It was cheaper to buy them as imports, and also, they would not have been readily available via domestic production. And they were planted densely, as we see from this excerpt from Areas of Desolation in Pennsylvania, by Joseph Trimble Rothrock (formerly Commissioner of Forestry of Pennsylvania), which came out in 1915:

“To plant an acre of young white pines 1,000 seedlings of say three years’ growth would not be an excessive number; in fact, 2,000 would be nearer the mark. They are started close, in order that in search for sunlight, tall, straight trunks may be developed. As they grow and crowd each other, the weaker ones are removed. The process of thinning continues until the timber has reached marketable size. From the time the young trees are 20 feet high they begin to have a value, and by sale of those removed, income (small at first) begins to come in.” (p. 21)

And so, as of 1909, imports of eastern white pine supplied the needs of the US, and they were planted by the millions, these immigrant plants, spreading industriously across the land. But this was not to last for long – shortly thereafter, the white pine blister rust decimated the importation of white pines, as it decimated the white pines themselves. White pine blister rust is a fungal disease of five needle pines. Pines are conifers, and they have needle shaped leaves, as do most other conifers. Pines, however, unlike other conifers, have their needles bundled together into what are called “fascicles”, with a papery sheath at the base of those bundles. There are, broadly speaking, two kinds of pines: five needle pines (Pinus strobus, the eastern white pine, is a five needle pine) and two-or-three needle pines (Pinus rigida and Pinus echinata, both mentioned above, are in this latter group). Within those groups, there are many kinds of pines, but every species of pine can be set into one of those two groups – they either have five needles, or two-or-three needles. And the white pine blister rust hits the five needle pines, and brutally. It came into North America around the turn towards the last century, sometime around 1900 (by 1906 it was definitively here), and it rapidly began to kill the white pines, and by the 1910s it was wiping them out. There were many responses to this botanical epidemic, but they were for naught, despite the best efforts of foresters across the nation. In addition to the general difficulties of controlling disease, which is always a sisyphean task, this was a time when the US, and the world entire, was incredibly strained. A summary of “The White Pine Blister Rust Situation”, published in Forest Leaves (published by the Pennsylvania Forestry Association) in 1919 covers this pretty well:

“We may congratulate ourselves, not on the measure of success with which our work has been carried out the past season but upon the fact that we have been able to work at all. The loss of men due to the draft, to war industries, the difficulties of housing and lodging, general increased expense of the work, the poor quality of much of the available help, and during the last two months the epidemic of influenza – all have greatly increased the difficulties of our work.”

There were a number of eradication efforts that were implemented as could best be done with the exigencies of the time, but most importantly for our story here, it was recognized that this disease had arrived via imported plants, and so a response, a major response, was an act of Congress – the Plant Quarantine Act of 1912. And “Quarantine No. 1” was against the white pine. The implementing language is as follows;

“Now, therefore, I, Willet M. Hays, Acting Secretary of Agriculture under authority conferred by section 7 of the act approved August 20 1912 known as the Plant Quarantine Act do hereby declare that it is necessary, in order to prevent the introduction into the United States of the White Pine Blister Rust, to forbid the importation into the United States from the hereinbefore named countries of the following species and their horticultural varieties, viz. white pine (Pinus strobus L.), western white pine (Pinus monticola Dougl.), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana Dougl.) and stone or cembrian pine (Pinus cembra L.)”

I include the above not simply as documentation, but because Hays was, I believe, the only writer ever to use more commas than I do. The rule continues:

“Hereafter and until further notice, by virtue of said section 7 of the act of Congress approved August 20, 1912, the importation for all purposes of the species and their horticultural varieties from the countries named is prohibited.”

And henceforth, importation of white pine seedlings was no more. This is not to say that white pines weren’t grown and sold in the US – they had been sold in the horticultural trade, and this continued to be the case throughout the time of the epidemic. In the 1900 Meehan’s catalogue (Meehan’s was a major nursery, located in Philadelphia), they write of the white pine that “This useful native species is very well known.” And the white pine was sold continuously in the horticultural trade, across the time of the Quarantine (Pinus strobus is in the 1906, 1907, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912, 1914, 1916, 1919 Andorra catalogs – Andorra was another major nursery, also in Philadelphia). [The above noted catalogs are at the McLean Library of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society] But the seedlings were no longer being imported, and the white pine was not a plant that had been grown in the US for large scale production. It was being grown for the relatively small amounts needed for horticultural plantings, but not by the millions that would’ve been needed to supply the needs of foresters. Because of this, white pines were not commonly planted for years after the Quarantine came along in 1912, as domestic production needed time to increase to meet the needs left wanting by the lack of imported materials. Even by 1915, US production was moving healthily forward, as is indicated in this excerpt from Rothrock’s Areas of Desolation in Pennsylvania:

“A senator of the United States, a gentleman who had made his fortune by lumbering, once stated in a public meeting in Washington that the white pine was doomed, that there was no help for it, that it could not be reproduced. In matters involving essential public policy, senators should be better informed. At the very hour of his utterance white pine seed, grown from mature trees in Germany, was being used in this country to produce seedlings for use in our forest nurseries. It is furthermore noteworthy that this imported white pine seed came from trees, or seeds, imported into Germany nearly a century ago from North America. It is fair to say that the white pine is among the easiest of our forest trees to reproduce. Forests of white pine, grown from nursery sown seed, are now well advanced on the Biltmore estate in North Carolina. The earliest plantation on the forest reserve at Mont Alto [this is in Pennsylvania] is now 15 feet high, and is in as thrifty a condition as any of natural growth.” (pp. 7-8)

As we see, by 1915, production was beginning to approach the needs of foresters, but they weren’t there yet. And in April 1916, in the magazine American Forestry (vol. 22), there is an advertisement published by Little Tree Farms of America (near Boston), for white pines, “The King of American Evergreens”,

“Use White Pine for screens, borders, avenue planting and otherwise beautifying an estate; for cutover lands; for sandy soils and other bare, unproductive, unsightly places; for worn out pastures; for lands useless for other purposes; for underplanting in shady places in woods where chestnut trees have died out. Plant groves of White Pine for restfulness.”

They charged $200 for a thousand trees, and $4.50 for ten of them. And so, beginning in 1912, after the Plant Quarantine Act, very few white pines were planted, and this remained the case for quite a few years thereafter, but it wasn’t long until domestic nursery production was rising to meet the needs of US planting. And by 1919, white pines were being distributed, free of charge, by the Commissioner of Forestry of Pennsylvania, as is noted in Forest Leaves (published by the Pennsylvania Forestry Association), in February 1919. [“The stock available for free distribution is almost all three years old and includes white pine, red pine, Norway spruce, European larch, Arbor Vitae, and a limited quantity of Japanese larch, and white ash.”]

The white pine stand in Cresheim Creek is roughly a hundred years old, and now, perhaps, it is clear why that “roughly” becomes interesting. It is now 2012. In October 2011, we cored a couple of trees in the white pine stand along Cresheim Creek (by “we” I mean John Vencius, Ned Barnard and me). For those two trees, we got, respectively: ages of 95 +/- years (dbh [diameter at breast height]: 29.3 inches) and 80 +/- years (25.5″ dbh). This puts the older one at right in the midst of the time when white pines were rarely planted, and right around the time when imports were banned. Coring of trees, like all endeavors scientific and otherwise, is not absolutely accurate – there is error associated with all measurements, and so we measure multiple times, and we measure multiple points, so that we can asymptote to reality. Therefore, at this point, with so few data points, we can only roughly say when this stand was planted – about a hundred years ago. And it leads us, or leads me at least, to ask some questions: Was this stand planted with seedlings imported from Germany? If so was it one of, if not the, last one planted in Philadelphia with imported seedlings? Or was it planted with seedlings produced domestically? If so, was it one of, if not the, first stands planted with domestically produced seedlings? I don’t know, and we don’t know, the answers to these questions, yet. If we knew everything, then researchers would all be out of work , and so, fortunately, there are always questions to ask, and there always will be, as long as there’s people to ask them. We’ll be looking at more of the trees in that stand, to see how old they are, and also looking for archival documentation of this stand’s planting, to see more closely when it was sown, to see on which side of the great divide of 1912 these plantings occurred.

There’s always questions to be asked, and often, too, there are answers to be had. We’ll see what those answers are, as they arrive. There is a larger question, however, that arises from these trees, I think, and that question is – what is natural? This stand of white pines in Cresheim Creek sits in the midst of Philadelphia, one of the largest cities in North America, and if most people were to walk among these trees, they would see it as an inspiring piece of nature’s work that somehow survives the urban impacts around it. After hearing that it is planted with a species of tree that is not native to Philadelphia, and that this stand was quite possibly planted with seedlings imported from thousands of miles and across an ocean away, and most certainly was planted with nursery grown seedlings from somewhere, and that it was quite likely planted for engineered erosion control, they might feel differently, might not feel that it’s natural. But these trees are here, and they are growing. They were planted a hundred years ago, or so – before I was born, before my parents were born, they were here. They’ll most likely be here long after I’m gone, too. Birds fly among them, squirrels climb in their branches, people walk under them. They’re seeding in offspring, seedlings coming up at their parents’ feet – being naturalized is in their nature. Someone, or more likely, someones, put them there, but now they thrive and survive on their own, set into an area along a creek that was a major industrial site, but no longer is, in the midst of one of the largest cities in the country, in a city that is thoroughly carpeted with concrete, this lush green forest rises above carpets of its own leaves, and you wouldn’t know its nature unless you looked very closely, at which point you see that this stand has created a little world all its own, and does make us think that, in this world, there’s a lot of ways to be natural.

Map by Nicole Wagner, graduate student in Geography and Planning, West Chester University, of the white pine stand along Cresheim Creek.

For more about trees of the Wissahickon watershed, see here: The white pines of Hermit Lane Hemlocks along the Wissahickon